1. Introduction

Drug discovery and development is a complex process requiring substantial time and financial investment. Projects typically begin by evaluating the relevance between targets and diseases, along with their potential for drug development, to select appropriate targets. Subsequently, decisions are made regarding the choice of drug delivery systems—whether traditional small molecules, biologics (such as antibodies or fragments), or novel approaches like antisense oligonucleotides and targeted protein degraders.

While drug efficacy and target-disease relevance are prioritized in pharmaceutical development, most project failures originate from safety concerns, with approximately 25%-50% attributable to inherent drug targets. This underscores the imperative of incorporating safety considerations into drug design. Safety risks vary across drug delivery systems: Small molecules may exhibit off-target chemical toxicity such as hERG channel inhibition or inhibition of hepatic drug transporters; antibodies and oligonucleotides could induce immunogenicity and/or nephrotoxicity (see Figure 1). Furthermore, target molecules themselves may generate adverse effects. When targets are expressed in both diseased and healthy tissues, pharmacodynamic amplification or tissue-specific differences may lead to targeted yet off-target toxicity. Previous studies have validated the value of Target Safety Assessment (TSA) in drug development, particularly in saving time and resources through early risk mitigation. This article will explore TSA generation and its application in drug development decision-making.

2. The Time and Significance of TSA's Implementation

TSA should be initiated early in drug discovery and development, or at any stage (see Figure 2).

1. Target selection phase: TSA identifies critical barriers, assists in comparing different targets to determine portfolio inclusion, and evaluates potential safety characteristics of drug forms (e.g., safety differences between antibodies and small molecules targeting the same target).

2. Lead compound optimization and candidate drug selection phase: A more comprehensive Toxicity and Safety Assessment (TSA) enables risk evaluation and development of risk mitigation strategies.

3. Subsequent research phase: TSA can interpret both non-clinical and clinical data.

With the growing number of drugable targets and drug forms, a deeper understanding of target biology and regulatory mechanisms has become increasingly crucial. Toxicology screening assays (TSA) have now emerged as a core tool for toxicologists in drug development.

Figure 2 contains several case studies:

1.NaV1.7 Target (Pain Therapy): NaV1.7 is predominantly expressed in neurons. Inhibiting it can modulate pain sensitivity, but its expression in olfactory sensory neurons may cause olfactory loss (acceptable side effect). However, related sodium channels may induce severe side effects such as long QT syndrome and epilepsy. Therefore, the project must achieve high specificity for the target.

2. Plastid enzyme targets (anti-malarial therapy): While plastid enzymes are specific and critical for Plasmodium, their limited selectivity for mammalian aspartic proteases may pose toxicity risks. It is essential to evaluate the effects of their inhibitors on human aspartic proteases, particularly CatD/E. If homology and mechanistic transferability between human and rodent targets are sufficiently demonstrated, early rodent studies should be initiated to assess risks.

3. Biotechnology project-related gait abnormalities: In a GLP toxicology study of rats, gait abnormalities emerged after 7 days of administration, initially attributed to central nervous system or muscular involvement. TSA analysis revealed the target protein's expression in skeletal tissues and its role in bone growth. Notably, this toxicity was observed exclusively in immature skeletal rats. Since the study mice were not fully mature, conducting TSA earlier could have predicted risks and avoided generating data irrelevant to clinical populations.

4. Clinical findings concerning a small molecule kinase inhibitor: The drug exhibited unexplained clinical outcomes with no clues from chemical structure analysis. TSA (Target Structure Analysis) indicated the effect originated from the target rather than the chemical structure. Therefore, the project must reassess the drugability of this target in the current indication.

3. TSA Generation Process

TSA is generated through three steps: "determine the source of evidence, screen relevant evidence, and evaluate the evidence to carry out risk assessment".

(1) Determining the source of evidence

1. Literature: Full-text analysis is required (key safety information may not be in the abstract), but full-text mining may be affected by OCR data loss (some early toxicology studies only exist as photocopies); conference reports and preprints are also channels for obtaining the latest target information.

2. Bioinformatics databases: Target-related asset information can be obtained from resources such as IUPHAR, Open Targets, or competitor intelligence sources.

(2) Screening relevant evidence

1. Novel targets: Mouse gene data (knockout/overexpression) and human genetic disease data (including OMIM database and GWAS findings) with target deletion or modification are valuable references.

2. Mature targets: While historical animal and clinical data (particularly publicly available approval information for marketed drugs) and toxicological data from failed projects are valuable, it is essential to confirm whether these results are relevant to the target.

3. The category effect or the result supported by multiple evidence should be preferred.

(3) Case Study: Application of Evidence Sources—Advantages and Potential Pitfalls

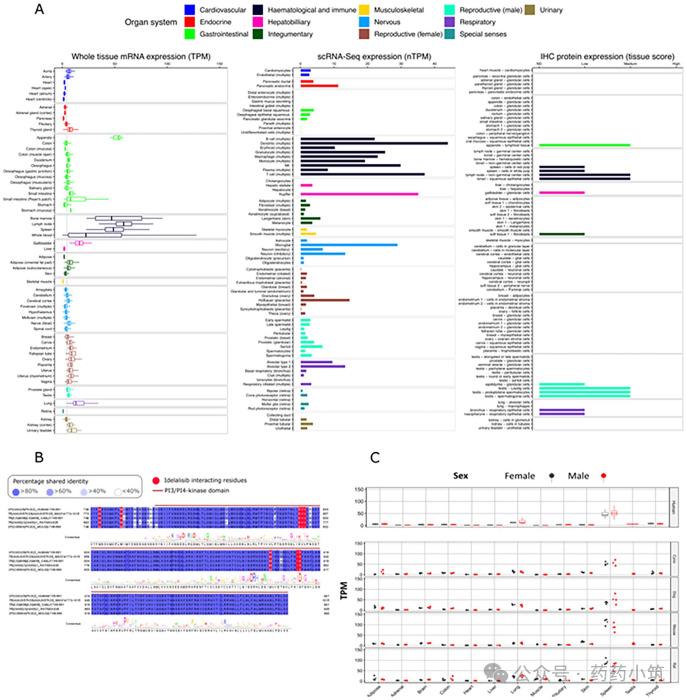

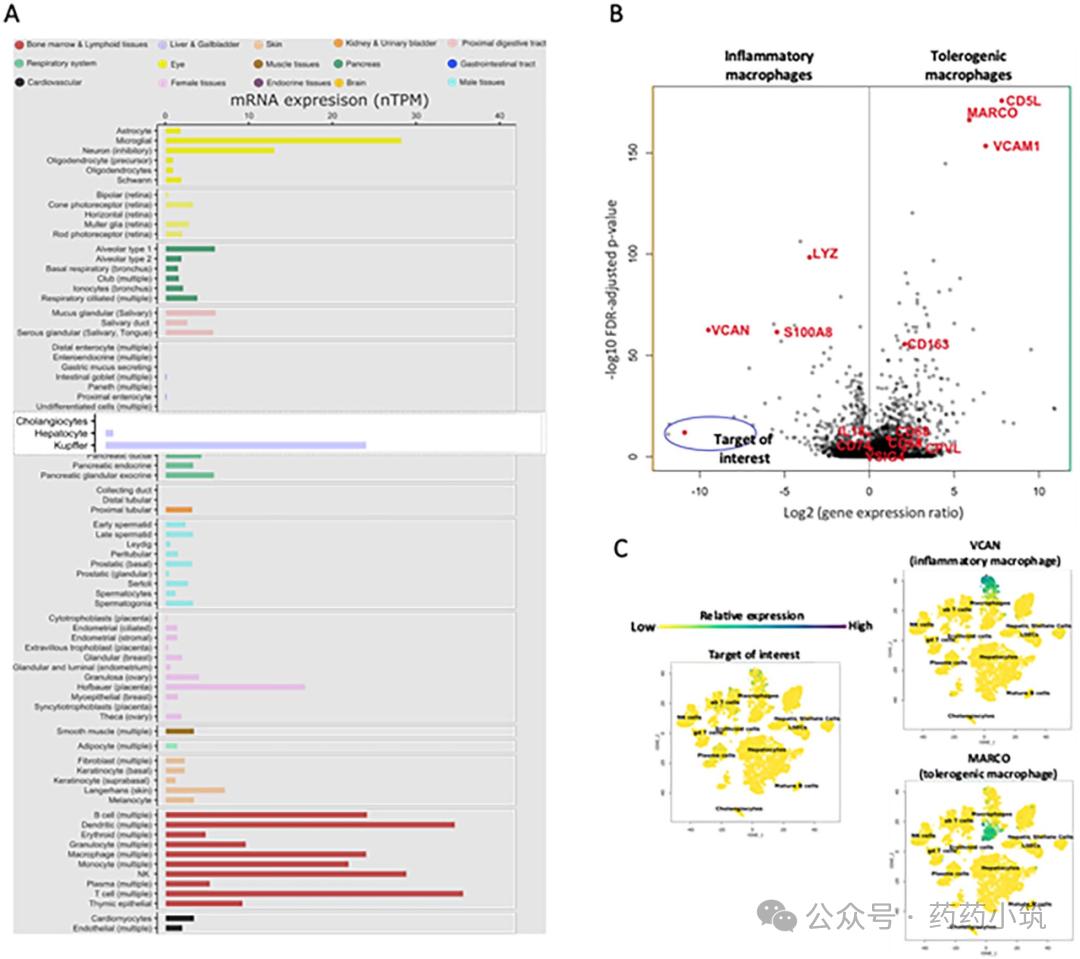

Taking PI3Kδ, a target approved by the FDA for oncology (Figure 3), as an example, TSA integrated gene and protein expression data from GTEx and HPA:

1. By integrating comprehensive whole-organ RNA sequencing data (with some tissue samples exceeding 100) alongside HPA's single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq) and immunohistochemical data, this study establishes a tripartite network to overcome limitations of single-platform approaches. Key challenges include: mRNA-protein expression correlations, immunohistochemical antibody reliability, and potential masking of high cellular expression by whole-organ sequencing – all effectively addressed by scRNA-Seq.

2. The results demonstrated that PI3Kδ was highly expressed in immune system and nervous system microglia, placental Hofbauer cells, and other tissues (though not reflected in immunohistochemical data). This analysis can identify potential target organs and cell types, providing references for evaluating cross-reactivity of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), identifying tissue-specific toxicity sites, and assessing safety risks of widely expressed targets across multiple tissues.

(4) Case Study: Cross-species Transformation Assessment

The translatability of target expression and function between preclinical species and humans is a critical prerequisite for successful drug development. Differences in these aspects may lead to intranslatable pharmacological effects or toxicological data irrelevant to humans. Therefore, Target Safety Assessment (TSA) must prioritize identifying genetic conservation (e.g., sequence homology) and mechanistic translatability (e.g., consistency in pharmacodynamics and toxicology) of targets. Early identification of interspecies differences in the project phase can prevent subsequent ineffective research and provide scientific basis for R&D direction.

1. P2X2/P2X3 targets (chronic pain treatment): The mechanism of action for this target was initially established through rodent model studies. However, TSA analysis revealed two critical differences: first, significant species-specific variations in pain mechanisms between rodents, non-human primates, and humans; second, distinct mRNA expression profiles and amino acid residues in the target's binding domain between rodents and humans, which directly impact the antagonist's binding capacity and therapeutic efficacy. Through TSA, these translational challenges were identified early, confirming that rodents are not the appropriate model species for this research project.

2.TYK2 target (autoimmune disease therapy): A single amino acid substitution in the ATP-binding pocket of TYK2 leads to significant differences in efficacy between human and preclinical species in novel TYK2 inhibitors. Sequence alignment of TYK2 across human, non-human primates, rodents, and canine species in TSA precisely identifies this critical variation, preventing redundant research efforts.

3. PI3Kδ Target (Oncology Therapy): TSA's bioinformatics analysis revealed that the drug-binding domain of PI3Kδ exhibits high similarity across humans, commonly used preclinical species (e.g., dogs), and mice in pharmacodynamic studies. Additionally, mRNA expression levels of this target showed remarkable consistency in 13 matching tissues between humans and preclinical species. Given the genetic conservation of key drug-binding domains, these findings support the conclusion that "this target demonstrates cross-species consistency in pharmacodynamics and tissue-specific responses, suggesting preserved mechanistic biological characteristics between preclinical species and humans," thereby enhancing confidence in data translation. However, it should be noted that even when data show consistency, literature review remains essential to supplement information on potential species differences and ensure comprehensive evaluation.

(5) Case Study: Limitations of Pre-organized Data

Pre-organized databases such as HPA, MGI, and Open Targets support TSA. For instance, HPA provides human protein distribution data, but since most of its data are compiled from other databases and literature, it may omit original discoveries or contain interpretive errors. Additionally, discrepancies in datasets may arise from reanalysis or direct use of the data.

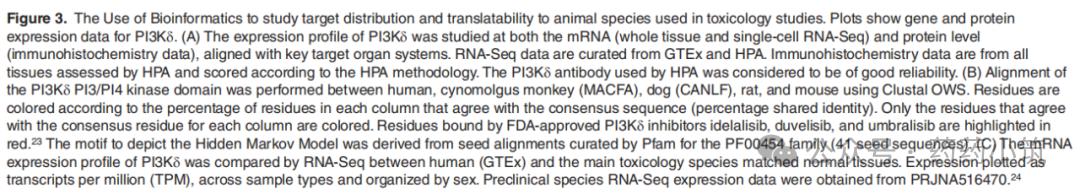

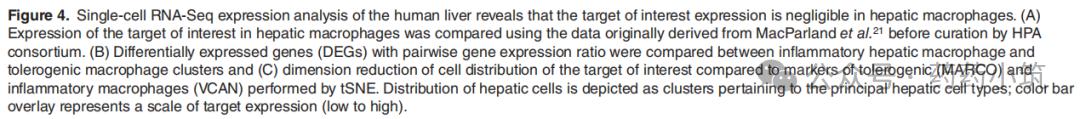

In a case study, the Human Protein Atlas (HPA, version 22) reported through single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq) that the target of interest showed high mRNA expression in liver-resident macrophages (Kupffer cells). This finding contradicted both the target's established biological role and previous literature conclusions, with no clear source of error identified. To resolve this issue, the research team avoided directly using HPA's pre-processed data. Instead, they conducted analysis through literature mining and raw data acquisition: They identified key marker genes VCAN and MARCO that distinguish pro-inflammatory from tolerant liver macrophages, and compared their expression patterns with the target (Figure 4). The results revealed significantly lower absolute mRNA expression (standardized per million transcripts, nTPM) of the target across multiple tissue macrophage populations compared to VCAN and MARCO. Additionally, HPA single-cell data showed enhanced expression of the target in various immune cells, with abnormal high expression in Kupffer cells. MARCO (a tolerant marker gene) exhibited high expression in common macrophages and low expression in Kupffer cells, while VCAN (a pro-inflammatory marker gene) showed high expression in Kupffer cells and low expression in common macrophages or monocytes, aligning with known cell-type-marker gene associations.

Through further analysis of metadata and literature, the study found that the original research did not directly process Kupffer cells but only labeled some cells as "non-inflammatory macrophages" based on their similarity to mouse Kupffer cells. Data clustering comparisons revealed that the target cell phenotype was more similar to pro-inflammatory macrophages (Cluster 4) rather than Kupffer cells themselves. When overlaying its expression onto the liver cell type atlas, the target was undetectable in all cell type clusters, while MARCO and VCAN were specifically expressed in corresponding macrophage subpopulations. Additionally, the original study authors noted that the liver cell homogenization method and experimental procedures used for scRNA-Seq analysis might influence result interpretation, as sorted cells' activity and heterogeneity could not reflect natural liver biological characteristics. Moreover, the five hepatic caudate lobe samples used were all from patients with neurological death and mild inflammation. To validate these conclusions, the study analyzed single-cell liver datasets from six healthy liver donors, finding that Kupffer cells were primarily divided into two subpopulations (Cluster 6: LIRB5+CD5L+MARCO+high HMOX1 expression; Cluster 2:...). In this dataset, the target was undetectable across 39 cell clusters, further confirming its no association with Kupffer cells or other liver cell types.

In conclusion, the original analysis may have shown an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and tolerant liver macrophage populations. Single-cell analysis results cannot accurately reflect the actual cellular proportions in healthy liver tissue. Errors during the processing of HPA single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq) datasets may have led to incorrect conclusions regarding target expression, thereby affecting the analysis of dehumanized but targeted binding risks in the liver.

IV. Summary

Drug design must incorporate safety considerations, addressing both toxicity associated with chemical structures/drug forms and unintended consequences of target modulation. The Therapeutic Innovation Society (TSA) continuously advances data science applications to assist in drug project identification and risk mitigation. Integration of target expression data and cross-species translatability assessments are critical for understanding the translation of pharmacological effects and safety profiles across species. Combined with drug form evaluations, these approaches can enhance decision-making and resource management. Such methodologies should be implemented early in drug development projects to guide decisions regarding target selection, chemical structure discovery, in vitro test selection, and exploratory in vivo research endpoints.

Disclaimer: This article is for knowledge exchange, sharing, and educational purposes only. It does not constitute commercial promotion, medical advice, or medication recommendations. If the content infringes on any rights, please contact us for removal.

Our product recommendations:

1.90182-92-6 https://www.bicbiotech.com/product_detail.php?id=6449

2.2245824-02-4 https://www.bicbiotech.com/product_detail.php?id=6450

3.1002309-52-5 https://www.bicbiotech.com/product_detail.php?id=6451

4.2244992-39-8 https://www.bicbiotech.com/product_detail.php?id=6452

5.113293-70-2 https://www.bicbiotech.com/product_detail.php?id=6453