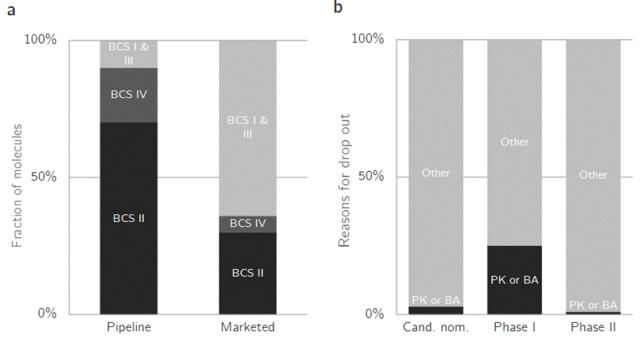

Approximately 40% of marketed drugs are poorly soluble. In early-stage drug development pipelines, this proportion is even higher, with nearly 70%-90% of candidate compounds exhibiting low solubility. This means a significant number of promising drug candidates are forced to halt development due to difficulties in effective dissolution and absorption in vivo. These drugs are predominantly classified as BCS Class II (low solubility, high osmotic pressure) or Class IV (low solubility, low osmotic pressure). BCS Class II accounts for approximately 70% of poorly soluble candidates, while BCS Class IV represents about 20%. The root cause of poor solubility lies in the high hydrophobicity and strong intermolecular forces of the molecules themselves, which are directly reflected in their structural characteristics such as high LogP, high melting point, and high rigidity. This is not merely a simple "solubility" issue but a systemic development challenge that triggers a cascade of adverse effects, including low bioavailability, high variability, difficulties in toxicological evaluation, and complex, costly formulation development. Therefore, in modern drug discovery, scientists employ computer-aided drug design (CADD) and high-throughput in vitro screening early on to optimize potency and selectivity while striving to mitigate these unfavorable physicochemical properties of molecules. The goal is to achieve a balance between "potency" and "drugability" at the molecular structure level. For poorly soluble candidates that cannot be avoided, early intervention is required to systematically evaluate and select the most appropriate formulation enhancement strategies to facilitate their successful passage through the development process.

Figure 1. Loss statistics in drug development. a Distribution of bioform classification system (BCS) categories in pipeline and marketed drugs, demonstrating significant losses in BCS II and IV drugs with low solubility. b Causes of losses during development. Due to incomplete exclusion of issues during candidate drug nomination, losses caused by pharmacokinetic or bioavailability problems are highest in Phase I clinical trials (up to 25%). To better facilitate drug formulation development, it is particularly crucial to identify potential challenges posed by poorly soluble drugs. This article will delve into the severe consequences that poorly soluble drugs may bring to drug development:

1. Low bioavailability and high variability:

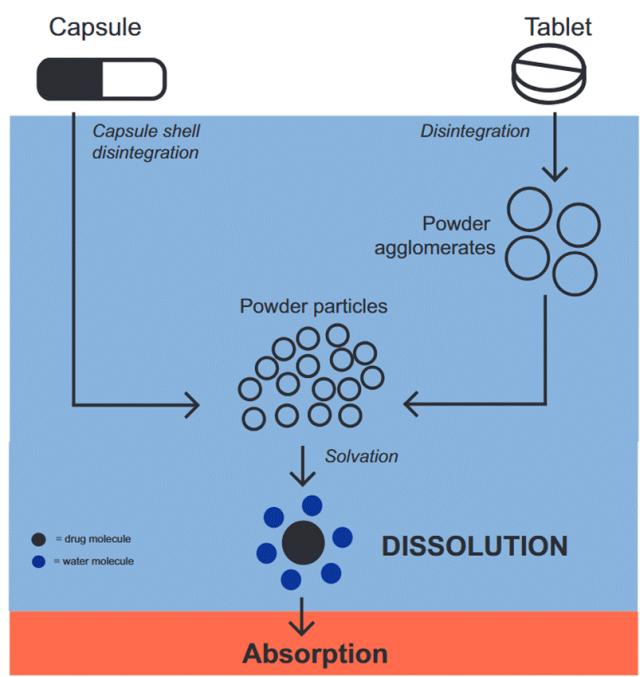

① Low bioavailability: It is well known that for oral drugs to enter the systemic circulation, they must undergo the following process: solid dosage form → disintegration → dissolution → dissolved drug molecules → transmemebrane passage → entry into the bloodstream. For drugs with good water solubility, the dissolution step is rapid and not a limiting factor, with absorption primarily dependent on permeability (transmembrane rate). However, for poorly soluble drugs, dissolution is the slowest and most limiting step in the entire process, becoming the "bottleneck" of absorption. Due to low solubility and slow dissolution rates, only a small fraction of the drug can dissolve within the limited time (typically several hours) required for drug passage through the absorption site (mainly the small intestine). As a result, the majority of the drug is excreted in the form of undissolved solids via feces, resulting in a very low fraction of the drug that can be absorbed (Fa). According to the formula F = Fa × Fg × Fh (where Fg and Fh represent the first-pass effects in the intestine and liver), the low Fa directly leads to a low absolute bioavailability (F).

Figure 2. Drug release process of tablets and capsules containing physical powder mixtures in the gastrointestinal tract. After entering the gastrointestinal tract, the tablets or capsules undergo disintegration initiated by water (blue portion). The capsules contain loosely packed powders, which come into contact with water once the capsule shell disintegrates. The tablets first disintegrate into large powder masses, which then further break down into fine powder particles. Ultimately, these fine particles disintegrate into individual drug molecules. Solvation occurs when water molecules surround the drug molecules, leading to drug dissolution. Only the dissolved drug molecules can be absorbed into the bloodstream (red portion).

② Unstable absorption rate (leading to significant variability): This is the primary source of variability. Dissolution rate is influenced by multiple physiological factors, which vary considerably among individuals and under different conditions. Gastric pH: For pKa-sensitive drugs (e.g., weak bases or weak acids), pH directly affects their solubility. Example: Weakly alkaline drugs exhibit higher solubility in the acidic gastric environment, but their solubility may sharply decrease after gastric emptying into the small intestine (pH ~6.5), leading to drug precipitation. The speed of gastric emptying (affected by food and individual differences) significantly impacts the duration of drug dissolution in the stomach, resulting in substantial variations in exposure. Food effect: Food significantly alters the gastrointestinal environment. Mechanisms: ① Delaying gastric emptying may increase or decrease the dissolution time of drugs in the stomach. ② Stimulating bile secretion: Bile salts in bile act as natural surfactants, enhancing the solubility of lipophilic drugs, which is beneficial for certain poorly soluble drugs but ineffective for others. ③ Altering intestinal peristalsis: Affects the retention time of drugs at the absorption site. ④ Direct drug interactions: High-fat foods may promote the dissolution and lymphatic absorption of lipophilic drugs. Result: For the same drug, the AUC and Cmax may differ by several times when administered on an empty stomach versus after meals, and this effect is unpredictable among individuals. Bile secretion and gastrointestinal motility: There are inherent differences in bile secretion volume, composition, and gastrointestinal motility speed among individuals. For drugs dependent on bile solubilization, individuals with low bile secretion may exhibit poorer absorption. Those with rapid gastrointestinal motility may have drugs excreted before they can fully dissolve and be absorbed.

2. Lack of dose proportionality:

What is dose linearity? Dose proportionality (Dose Proportionality) refers to the phenomenon where a key pharmacokinetic parameter (primarily AUC) corresponding to drug exposure increases proportionally by a factor X when the administered dose is increased by X-fold. For example, if the dose is doubled from 50 mg to 100 mg, the AUC also increases from 100 ng·h/mL to 200 ng·h/mL (a 2-fold increase). At low doses, the drug may be fully dissolved and absorbed. However, as the dose increases, the dissolution process reaches saturation, and absorption no longer increases proportionally, resulting in the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) failing to grow linearly with the dose. This poses significant challenges in clinical dose exploration. To illustrate with a metaphor: Imagine using a strainer (intestinal tract) to catch water (drug) flowing from a faucet, with the goal of collecting the water (AUC) in a cup within a specified time. At low doses (thin faucet flow), all water can pass through the strainer's holes (dissolution) and drip into the cup. When the flow rate doubles, the amount of water collected doubles (dose proportionality). At high doses (full faucet flow), the water flow becomes too rapid for the strainer's holes (solubility/dissolution rate) to accommodate all the water, causing most of the water to flow directly through the edges of the strainer (excreted with feces). At this point, even if the faucet is turned up further (increased dose), the amount of water passing through the holes (absorption) remains almost unchanged because the strainer's capacity has reached saturation (lack of dose proportionality).

3. Impaired preclinical safety evaluation:

Toxicological studies require administering animals extremely high doses to identify the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and the no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL). To achieve these objectives, animals must be given doses sufficiently high to ensure the observation of potential toxic effects. These doses are typically far exceeding the anticipated clinical therapeutic doses. For soluble drugs, increasing the dose often leads to a proportional rise in systemic exposure (e.g., AUC, Cmax) until the MTD is reached. However, for poorly soluble drugs, due to their low solubility and slow dissolution rate, absorption exhibits a clear "ceiling" or "saturation point." Once the dose exceeds this threshold, the exposure no longer increases. If a drug is poorly soluble and cannot achieve sufficiently high exposure levels in animals through conventional methods (e.g., suspensions), its toxicity cannot be adequately evaluated, potentially leading to the failure of promising drug candidates due to incomplete toxicological studies.

4. High difficulty, cost, and long cycle in formulation development:

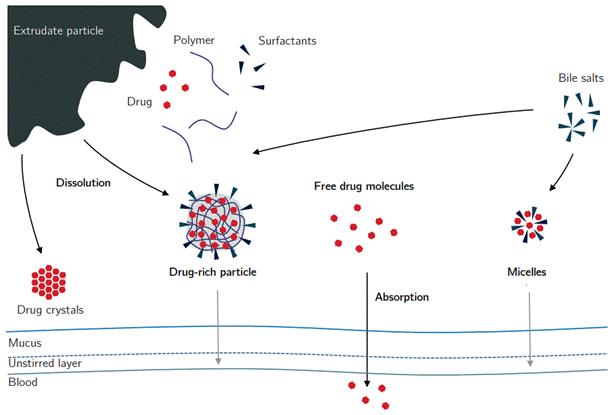

Complex and expensive "enabling formulations" such as nanocrystals, amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs), lipid-based formulations (SEDDS/SMEDDS), and complexes (cyclodextrins) must be employed. These technologies involve intricate processes, pose challenges in scale-up production, and require rigorous solid-state research and formulation screening, significantly increasing development time and costs. For instance, amorphous solid dispersions face physical stability risks (recrystallization), while nanocrystals encounter issues like Ostwald maturation and particle aggregation.

<span lang= "EN-US" style= "font-family:" Times New Roman ",serif; mso-fareast-font-family:<p>Songti; mso-no-proof:yes;"><span leaf=; "" = "">

Figure 3 In vivo behavior of solid dispersions

5. Poor intravascular-to-intracorporeal correlation (IVIVC):

Due to the extremely slow dissolution of drugs, the "dissolution" step becomes the most bottleneck-limited phase of the entire process. This means that the rate and extent of drug absorption in vivo are entirely dependent on its dissolution rate and extent. Theoretically, this should serve as the ideal foundation for establishing a robust IVIVC (in vivo-in vitro comparison), as the in vivo absorption curve (inferred from the plasma concentration curve) should be directly correlated with the in vitro dissolution curve. However, since dissolution is the rate-limiting step, even minor changes in in vitro dissolution conditions (medium, rotation speed) can lead to significant variations in dissolution behavior, making it difficult to accurately predict in vivo behavior from in vitro data and posing challenges for quality control. A slight misstep in in vitro methods can result in "sky-high" differences in dissolution results, lacking robustness. Specific conditions that may vary in vitro include:

Solvent pH: For pKa-sensitive compounds (e.g., weak acids or weak bases), a 0.1-unit change in solvent pH may cause a significant percentage-level alteration in solubility, thereby fundamentally altering the dissolution profile.

Surfactant concentration: To simulate the solubilization effect of bile, a small amount of surfactant (e.g., SDS, Tween 80) is often added to the in vitro dissolution medium. A slight variation in concentration from 0.1% to 0.5% can significantly alter the wetting property and solubility of the drug, potentially doubling or sharply reducing the dissolution rate.

Rotational speed/stirring efficiency: The difference in paddle rotation speed of the dissolution apparatus (e.g., 50 rpm vs 75 rpm) alters the thickness of the liquid hydrophobic layer on the drug particle surface, thereby significantly affecting the diffusion rate. For drugs with inherently slow dissolution, this difference is amplified.

Medium ionic strength: Variations in ionic strength may affect the solubility of drugs (salt effect) and the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of surfactants.

6. Commercialization challenges:

The final formulation may be bulky (e.g., requiring multiple capsules or large tablets) or necessitate special packaging and storage conditions (e.g., moisture-proof, refrigerated), which can affect patient compliance and the product's market competitiveness. Insoluble drugs often exhibit low potency, meaning a larger absolute dose (e.g., 200 mg or even 500 mg) is required to achieve therapeutic effects. Most advanced solubilization technologies (e.g., solid dispersions, nanocrystals, lipid formulations) incorporate substantial amounts of functional excipients. For instance, solid dispersions require large quantities of polymers (e.g., HPMC, PVP) to stabilize amorphous drugs. In the final product, the proportion of API (active pharmaceutical ingredient) (drug loading) may be as low as 10-30%. A 200 mg dose, with a drug loading of only 25%, may have a total mass of up to 800 mg when excipients are included. This far exceeds the standard 00 capsule capacity (approximately 600 mg), potentially requiring the filling of two extra-large capsules or even three standard capsules. For tablets, the formulation may need to be compressed into an oversized tablet that is difficult for patients to swallow.

Case: Olaparib is a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PRAP) inhibitor, and the inhibition of PARP can cause cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase, ultimately inducing apoptosis. Due to the poor solubility of olaparib, advanced drug delivery technologies are required to ensure bioavailability. The initially approved dosage of 400 mg was administered in eight 50 mg capsules twice daily. Subsequently, a hot-melt extrusion tablet formulation (developed as a solid dispersion) was developed to improve the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of olaparib and reduce the patient's dosing burden. The recommended tablet dosage is 300 mg twice daily (two 150 mg tablets).

The excessive volume of the formulation imposes a heavy medication burden on patients: multiple daily doses requiring swallowing of large capsules or tablets, which causes discomfort and resistance in patients (particularly elderly individuals and those with dysphagia); complex packaging (e.g., requiring self-assembly) and stringent storage conditions (e.g., mandatory refrigeration) are prone to patient errors (such as forgetting to refrigerate or misadministering doses), potentially compromising efficacy and even posing safety risks. Poor adherence directly leads to reduced clinical efficacy, as evidenced by suboptimal performance in real-world studies.

The complex manufacturing processes (such as hot-melt extrusion, high-pressure homogenization, and spray drying) and specialized packaging materials (high-barrier packaging, desiccants) result in significantly higher production costs compared to conventional tablets. These elevated costs are ultimately passed on to payers (health insurance, patients), rendering drug prices uncompetitive. If alternative therapies are available in the market (even if they are less effective but more affordable conventional formulations), patients and physicians may opt against this "expensive and difficult-to-use" medication. The cumbersome administration requirements may label the product as "user-unfriendly," adversely affecting its market reputation and acceptance.

In conclusion, the emergence of poorly soluble drugs is inevitable, and practical challenges do exist. Recognizing these difficulties while advancing courageously is the attitude that pharmaceutical formulators should adopt. More importantly, it is crucial to master ingenious strategies and innovative approaches to overcome these obstacles. The road ahead is long and arduous, but I shall persistently seek solutions with unwavering determination.

References

1.Amorphous Solid Dispersions as Oral Delivery System for Poorly Soluble Drugs–Mechanistic and Translational Research

2.Solid dispersions in oncology: a solution to solubility-limited oral drug absorption

3.Development and Production Application Cases of Amorphous Solid Dispersion Formulations (I) - Hot Melt Extrusion

Disclaimer: This article is intended solely for knowledge exchange, sharing, and popular science purposes, and does not constitute commercial promotion, nor should it be regarded as medical guidance or medication advice. For copyright infringement, please contact us for removal.

Our product recommendations:

1.102029-73-2 https://www.bicbiotech.com/product_detail.php?id=6487

2.1926-57-4 https://www.bicbiotech.com/product_detail.php?id=6488

3.54120-64-8 https://www.bicbiotech.com/product_detail.php?id=6489

4.3406-02-8 https://www.bicbiotech.com/product_detail.php?id=6490

5.3238-40-2 https://www.bicbiotech.com/product_detail.php?id=6491